Selvom voldgift hviler på en grundlæggende forudsætning om, at parterne skal kunne vælge den eller de voldgiftsdommere, som de anser for bedst egnede til at afgøre deres tvist, er det ikke altid nok blot at forholde sig til en kandidats faglige profil eller erfaring med voldgift. For at finde den rette kandidat bør man som part samlet vurdere såvel kandidatens faglige som personlige egenskaber for at øge sandsynligheden for, at ens synspunkter i det mindste bliver hørt og drøftet korrekt under voteringen. Det er som bekendt ikke tilstrækkeligt at have ret – det handler også om at få ret, skriver Frederik Kromann Jespersen.

Af Frederik Kromann Jespersen, partner Skau Reipurth

For det kollegiale panel af voldgiftsdommere er voteringen ofte et af højdepunkterne i sagen. Det er tidspunktet, hvor man som voldgiftsdommer får mulighed for at drøfte sin og sine dommerkollegers opfattelse af sagens relevante tvistepunkter på baggrund af de beviser og synspunkter, som parterne henholdsvis har fremlagt og gjort gældende. Det er et stort privilegium at kunne diskutere et emne intensivt med andre, som (i hvert fald i et afgrænset tidsrum) har samme interesse for emnet og samme grundlag for at diskutere det.

Principielt er der næppe de store forskelle mellem votering ved de almindelige domstole og i forbindelse med en voldgiftssag. Voldgift er dog kendetegnet ved parternes mulighed for selv at udpege den eller de personer, som skal fungere som voldgiftsdommer(e) under sagen, og selvom en part givetvis har stor interesse i at udpege den fagligt set mest kvalificerede kandidat, bør parten også overveje, hvordan kandidaten må forventes at kunne indgå i voteringen. Uanset faglig dygtighed kommer man ikke udenom, at voteringslokalet til tider også får karakter af et forhandlingslokale, hvor sagens resultat eller måske begrundelsen derfor skal ”bokses” på plads, og dommerens evne til at indgå i sådanne forhandlinger kan nemt have betydning for vedkommendes muligheder for at få sit synspunkt igennem over for de andre dommere.

Emnet for dette indlæg er at sætte nogle ord på den typiske voteringsproces og de overvejelser, som en part i en voldgiftssag, der skal afgøres af flere partsudpegede voldgiftsdommere, bør gøre sig om en given kandidats – forventede – forudsætninger for at kunne gøre sig gældende under voteringen, inden parten formelt udpeger vedkommende som voldgiftsdommer.

Formålet med og tilrettelæggelsen af voteringen

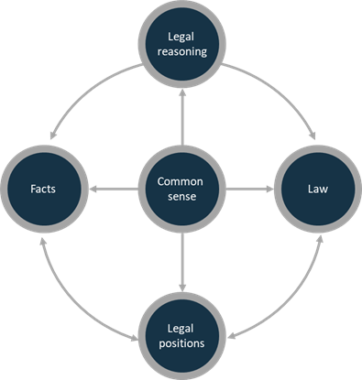

Det overordnede formål med voteringen er at drøfte – og sortere i – de beviser og juridiske synspunkter, som parterne henholdsvis har fremlagt og gjort gældende til støtte for et bestemt resultat i lyset af sagens faktiske omstændigheder. Til tider kan det også være nødvendigt at drøfte forhold, som voldgiftsretten ex officio har måttet adressere og italesætte over for sagens parter.

Voldgiftsdommerne bør under voteringen sikre, at alle relevante synspunkter drøftes, herunder at de respektive synspunkter kan føre til det resultat, som hver part har plæderet for i lyset af partens påstand(e). Det er som oftest formanden for voldgiftsretten, som konkret fastlægger, hvordan voteringen skal foregå, og der kan være stor forskel på, hvordan dette sker i praksis. Hvis formanden har en faglig baggrund som dommer ved de almindelige domstole, kan der være en tilbøjelighed til, at voteringen kommer til at foregå på samme måde som ved domstolene, dvs. at den yngste dommer typisk voterer først. Hensynet bag denne ordning er navnlig at sikre, at den yngste dommer stilles frit i forhold til sit votum og ikke føler sig ”tvunget” til at votere for et specifikt resultat, som en ældre dommer måtte have voteret for.

Andre formænd er af den opfattelse, at netop dommeren med længst anciennitet bør votere eller i hvert fald tilkendegive sin opfattelse først for derved at øge sandsynligheden for, at de øvrige dommere fra starten spores ind på de – efter den førstevoterendes opfattelse – relevante, juridiske synspunkter og bevistemaer. Hvis en eller flere af voldgiftsdommerne derimod har for eksempel en teknisk – modsat en juridisk – baggrund, og hvis sagens omdrejningspunkt er teknisk kompliceret, kan voteringen også være tilrettelagt på den måde, at netop den eller disse dommere skal votere først for derved at søge at sikre, at sagens tekniske omstændigheder fastlægges korrekt og indledningsvist.

I praksis forekommer det dog nok oftest, at voteringen foregår som en fri (men styret) dialog mellem voldgiftsdommerne – eventuelt hjulpet på vej af en dagsorden, som typisk formanden for voldgiftsretten på forhånd har udarbejdet. Denne fremgangsmåde er selvsagt den mindst rigide og er egnet til at sikre, at dommerne løbende kan adressere forskellige synspunkter og afstemme, hvorvidt man er enig i bedømmelsen af rækkevidden af det pågældende synspunkt i forhold til det resultat, som en part har plæderet for. Afhængigt af sagens kompleksitet og de konkrete omstændigheder kan også formuleringen af præmisserne i voldgiftskendelsen helt eller delvist fastlægges under voteringen. Sædvanligvis udarbejder voldgiftsrettens formand et udkast til kendelse på baggrund af drøftelserne under voteringen, som de øvrige voldgiftsdommere efterfølgende får lejlighed til at kommentere.

Voteringen er en meget koncentreret proces, som kun lader sig gennemføre effektivt, hvis samtlige voldgiftsdommere har forberedt sig grundigt og er deltagende i processen. Dette er dog efter min erfaring også tilfældet i langt de fleste sager, og jeg oplever ofte, at man på trods af en sags kompleksitet og omfang ret hurtigt får afstemt, hvorvidt der er enighed om resultatet og dets begrundelse allerede under de indledende voteringsdrøftelser. Det er selvfølgelig ikke ensbetydende med, at forhold ikke senere kan genbesøges (f.eks. i forbindelse med udarbejdelsen af præmisserne i kendelsen), eksempelvis hvis en voldgiftsdommer har tilkendegivet, at vedkommende voterer under tvivl i forhold til et eller flere forhold under sagen.

Hvis én af voldgiftsdommerne er uenig i de øvrige dommeres bevisvurdering eller resultat (eller måske blot begrundelsen derfor), kan vedkommende principielt afgive dissens. Denne mulighed er i praksis nok forbeholdt de situationer, hvor en dommer vitterligt ikke kan ”se sig selv” stemme for flertallets resultat eller begrundelse, og erfaringsmæssigt skal der meget til, før en voldgiftsdommer insisterer på at dissentiere. Som regel kan uenigheder om sagens resultat eller begrundelsen derfor løses hen ad vejen.

Udpegning af voldgiftsdommeren med sigte på voteringen

Som nævnt får voteringen ofte karakter af en forhandling, hvor voldgiftsdommerne drøfter forståelsen og rækkevidden af sagens relevante beviser og juridiske synspunkter. Som ved enhver anden forhandling afhænger den enkelte voldgiftsdommers mulighed for at overbevise sine meddommere om et givet forhold blandt andet af vedkommendes erfaring, faglige profil og personlige gennemslagskraft. Som den part, der skal udpege en voldgiftsdommer, bør man ikke være blind for denne kendsgerning.

Voldgift er en traditionsbunden disciplin og har længe været kendetegnet derved, at ældre personer med solid erfaring inden for voldgift ofte udpeges som voldgiftsdommere. Som part kan man derfor være bekymret for at udpege en yngre kandidat af frygt for, om vedkommende kan gøre sig gældende under voteringen. Men den bekymring kan let være ubegrundet – navnlig hvis den yngre kandidat er fagligt velfunderet i forhold til de (måske tekniske) forhold, som sagen vedrører. En parts valg af voldgiftsdommer kan dermed i høj grad være påvirket af, hvem de øvrige dommere i panelet er eller må forventes at være. Der kan være situationer, hvor man som part ikke ved, hvem modparten udpeger som voldgiftsdommer, når man selv har udpeget sin voldgiftsdommer, f.eks. når man som klager afventer indklagedes svarskrift med oplysning herom, jf. Voldgiftsinstituttets Regler for behandling af voldgiftssager (§ 13, stk. 1, litra k). Men i praksis er det som oftest klart, hvem eller hvilken type modparten vil eller må forventes at udpege.

Det interessante spørgsmål er selvfølgelig, hvilken kandidat man bør pege på. Og det nemme (og helt uanvendelige, generiske) svar er, at det afhænger af den konkrete sag. Klart er det dog, at hvis sagen hovedsageligt er en juridisk tvist om for eksempel forståelsen af et sæt aftalevilkår, er der som udgangspunkt næppe meget vundet ved at udpege en voldgiftsdommer, som ikke har juridisk baggrund. Omvendt er det klart, at en voldgiftsdommer med juridisk baggrund kan komme til kort, hvis sagens omdrejningspunkt hviler på den praktiske forståelse af en branchesædvane. Også vedkommendes sproglige kundskaber såvel skriftligt som mundtligt kan have afgørende betydning – ikke mindst i en international voldgiftssag. Det kan være vanskeligt at opnå gennemslagskraft under voteringen, hvis det kniber med at gøre sig forståelig.

Selvom voldgift hviler på en grundlæggende forudsætning om, at parterne skal kunne vælge den eller de voldgiftsdommere, som de anser for bedst egnede til at afgøre deres tvist, er det ikke altid nok blot at forholde sig til en kandidats faglige profil eller voldgiftsmæssige erfaring. For at finde den rette kandidat bør man som part samlet vurdere såvel kandidatens faglige profil som personlige egenskaber for at øge sandsynligheden for, at ens synspunkter i det mindste bliver hørt og drøftet korrekt under voteringen. Det er som bekendt ikke tilstrækkeligt at have ret – det handler også om at få ret.

Frederik Kromann Jespersen

Advokat (H), partner i advokatpartnerselskabet Skau Reipurth. Forfatter til bogen Vidneafhøring, der er udgivet på DJØF Forlag.